Hatcheries in Southeast Alaska release millions of salmon fry every year. When those fish are caught years later, determining where they hatched is critical for fishery managers. Since the 1990s, hatcheries have used otolith marks to encode that information in every fish they release.

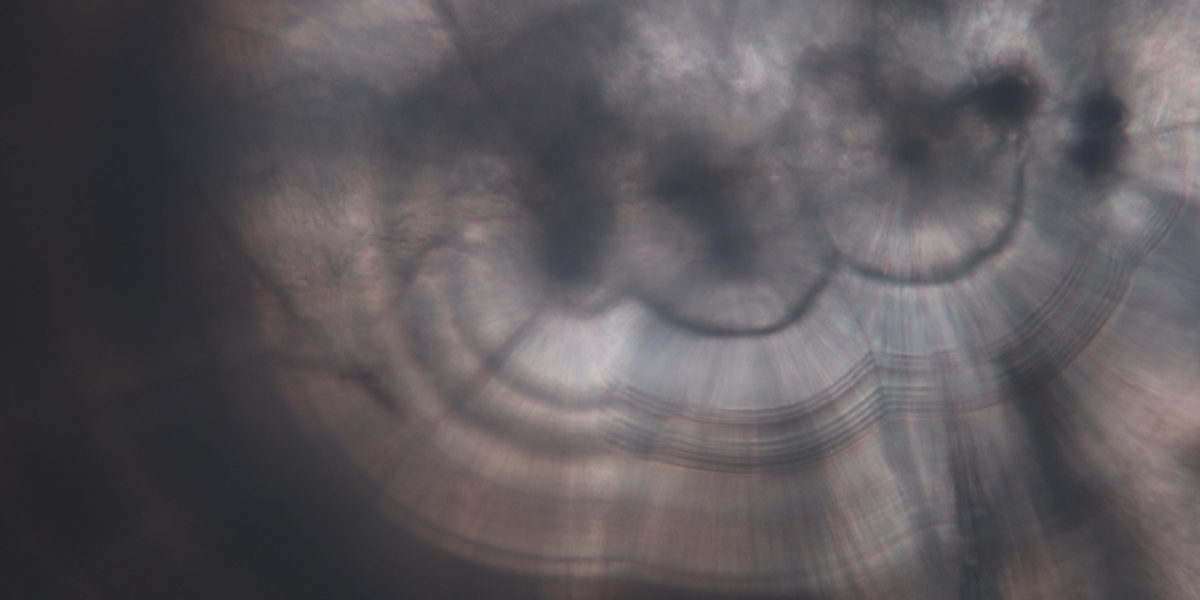

An otolith is a bone-like calciferous structure found in the ears of many animals, including salmon. The structure grows throughout the fishes life depositing patterns similar to tree rings as it does. In the case of otoliths, dark and light rings occur when the fish is exposed to any of a variety of stressors. Hatcheries take advantage of this by manipulating the temperature of their water in a predetermined pattern. The result is a “bar code” deposited inside the otolith that persists throughout the fish’s life.

Otolith Marking and Reading Research (OMARR)–a small research organization in Ketchikan, Alaska–contracted Kempy Energetics to develop a computer program to distinguish between marks in digital images of otoliths. Although not directly related to energy, the project leverages Kemp’s background in mathematics and computer modeling to solve a regional challenge. An automated method for distinguishing between marks will not reduce the cost of classifying otoliths by much–the majority of the cost is associated with preparing the otolith for imaging rather than the classification itself. However, automated classification will generate more reproducible and perhaps more reliable results than human readers. Future work may use machine learning to identify patterns in wild fish stocks that have not been recognized by humans.